No matter what type of work is done in a laboratory, it’s almost certain that lab water is required to carry out certain processes. Due to the sensitive nature of laboratory work — and the need for as many factors to be controlled as possible for effective, accurate testing and research — lab water must be pure, with defined levels of acceptable impurity.

The types of water used in laboratory processes and settings are defined, by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), into four grades: Type I, Type II, Type III and Type IV. While ASTM designations are the most commonly used, water purity levels are important enough that there are also ISO and CLSI-CLRW standards. Throughout the rest of this piece, we will refer to the types of water used in laboratory work by the ASTM designations. Next, we’ll look at the properties that define water purity.

Definitions of Water Purity

There are several factors that define water purity, which are critical to distilled water types:

- Conductivity: Typically used for less pure water types (Type III and Type IV), conductivity measures the ease with which a water sample conducts electricity. Because electricity is conducted through ionic content in water, conductivity measures how much of this content is present.

- Resistivity: Normally used for more pure water types (Type I and Type II), resistivity measures how difficult it is for electrical current to travel through a water sample. The more difficult it is (and the higher resistance), the less ionic content is in the water, making for a purer sample.

- Total organic carbon (TOC): Total organic carbon is an efficient way to measure the amount of organic material present in water through carbon testing. As an aggregate reading, total organic compound provides an accurate general measurement of the purity of a water sample in terms of microorganisms and other organic material present.

- Turbidity: Turbidity — or water clarity — is able to provide a rough sense of water purity in terms of contaminants and other material present. It is useful for the lower purity grades — Type III and Type IV.

Types of Pure Water

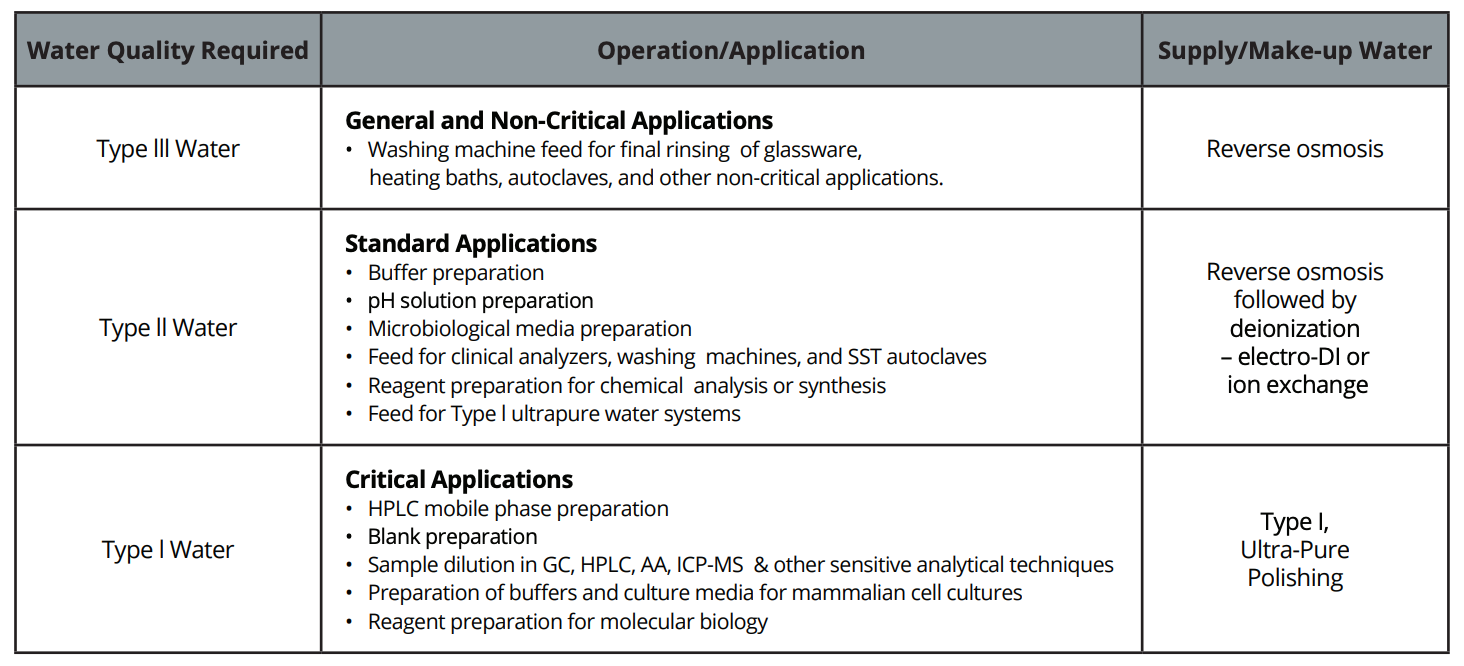

This section describes the types of pure water as defined by ASTM. We will also provide examples of applications for each.

Type I: The purest type of water — used for cell culturing, gas chromatography, HPLC, tissue culturing, mass spectrometry and any other process requiring the highest levels of purity. Type I lab water is considered “ultrapure,” and must meet the following requirements:

- Resistivity: Greater than 18 MΩ-cm

- Conductivity: Less than 0.056 µS/cm

- Total organic carbons: Less than 50 ppb

Type II: Not considered “ultrapure,” but still pure enough for specialized use, Type II is used for clinical analyzers, instrument feeds, electrochemistry and direct sample dilution — as well as for a feed to create Type I water. Type II water meets the following standards:

- Resistivity: Greater than 1 MΩ-cm

- Conductivity: Less than 1 µS/cm

- Total organic carbons: Less than 50 ppb

Type III: Produced from standard tap water using reverse osmosis, Type III water is a lower level of purity more suited for general use and as an initial stage for Type I or Type II water. Type III is used in rinsing and other preparation and secondary tasks. Type III water has the following properties:

- Resistivity: Greater than 4 MΩ-cm

- Conductivity: Less than 0.25 µS/cm

- Total organic carbons: Less than 200 ppb

Type IV: Most often used as a feed to create more pure water, Type IV water is produced through reverse osmosis to the following specs:

- Resistivity: 200 KΩ-cm

- Conductivity: Less than 5 µS/cm

- Total organic carbons: No standard

As you can see, lab water purity measurements are complex. These requirements are, however, critical to the integrity and accuracy of your processes and results, as well as your certifications.

TSS is experienced in measuring and certifying lab water purification systems and tools to help ensure your water is up to spec. For more information, view our services or contact us today.